Frida Wannerberger: The Dinosaur

Tree

9 January - 5 February, 2026

Private View: Thursday, 8 January, 6-8pm.

LBF Contemporary is pleased to announce ‘The Dinosaur Tree’ - an exhibition of new works by Frida Wannerberger.

The Dinosaur Tree

By Salomé Jacques

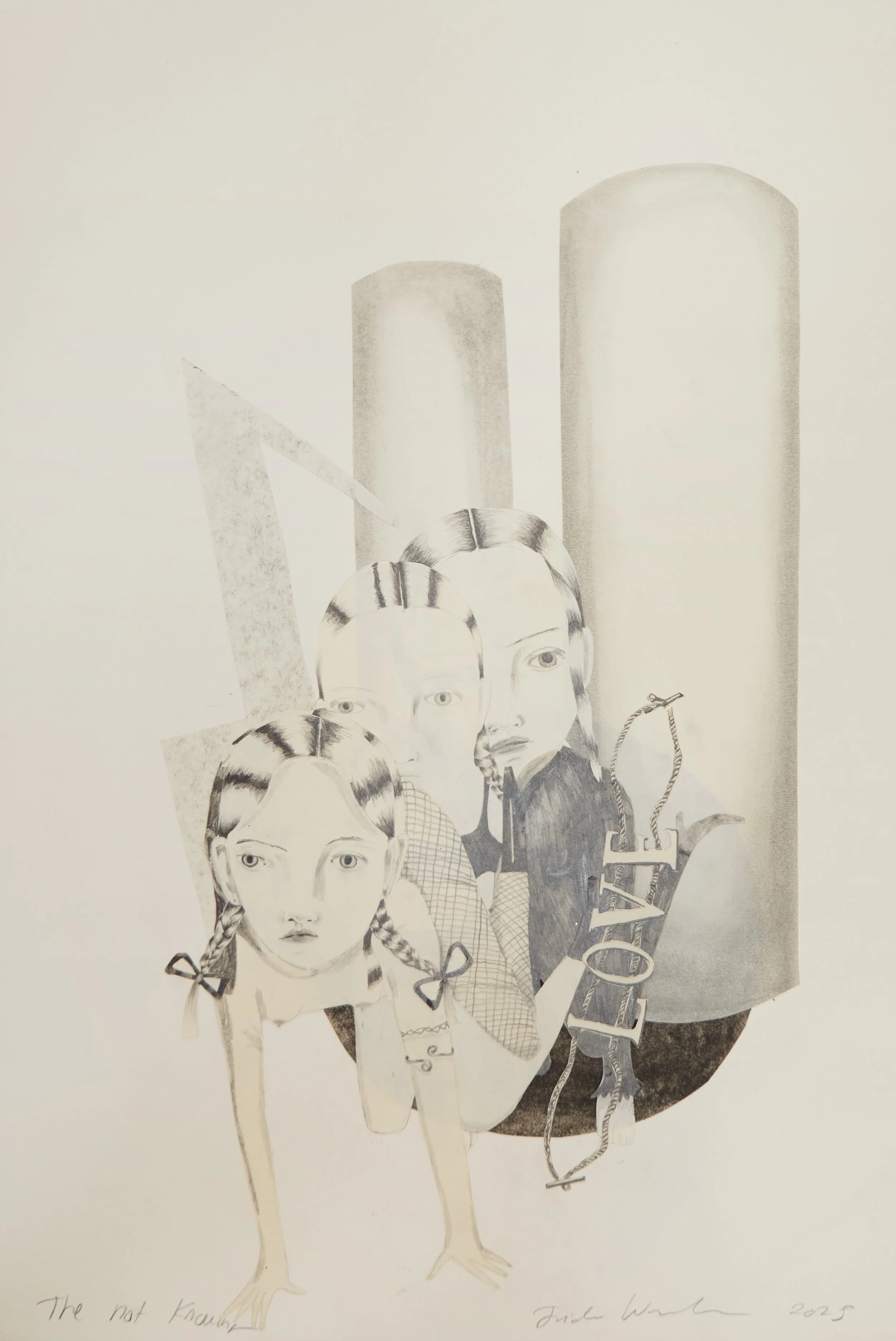

Part folkloric tale, part autobiography, The Dinosaur Tree is Frida Wannerberger’s most personal work to date. Documenting months of private reflection, the drawings and paintings function as visual chronicles of an ever-expanding story. Invoking the private language expressed in a secret diary, the artworks presented at LBF Contemporary recall the freedom that pen and paper (or brush and canvas) offer to the beholder. In this spirit, the title refers to the image of the dinosaur tree, recurrent throughout the body of work. Once witness to two people who shared a romantic intimacy, the dinosaur tree becomes part of a lexicon that once formed a shared language. As emotions are expressed without prejudice or judgement, The Dinosaur Tree retains the sanctity of a shared communication only understood by two people who were intimate.

The exhibition’s storytelling begins with the prospects of intimacy, and remarkably expands into a commentary on sex, love, romance, deception and loss. Constructed around distinct ‘scenes’, each work introduces two protagonists: the ‘submissive/complacent/docile girl’ and the ‘naughty girl rebelling against the male gaze’.

The ‘submissive/complacent/docile girl’ represents a side that wants to please, seeks to transform herself into an object of desire for a man to love. She submits and obeys to fantasies. Although she carries it like an armour, the bondage harness she wears adorns her body: will pleasing him make him stay? By contrast, the ‘naughty girl rebelling against the male gaze’ resists such expectation by adopting ‘unfeminine’ behaviours – asserting dominance, existing loudly and turning herself into an unattractive, even frightening figure. Her very presence makes us wonder: to what extent are women defining their own sexuality? Are women surrendering their power in order to please men? Is giving in to sexual fantasies losing our independence? Titles such as Dirty Little Bitch and We Should Dress You Like a Whore remind us of the underbelly of misogyny and the intricate ways in which violence and degradation are embedded in the language and attitudes through which women are addressed and perceived.

Playing on the dichotomy of ‘good’ versus ‘evil’, the two figures form a harmonious pair. Questioning the very principles of psychoanalysis, they recall and destabilise the infamous ‘madonna-whore’ complex, which frames women as either virtuous or sexual. By manifesting their own personalities, they resist such characterisation and instead embrace sexuality on their own terms. While self-objectification through sexual expression in the public realm has been seen as subversive, Wannerberger embraces it to interrogate the power dynamics that shape heterosexual relationships. Britney Spears said it best in her book The Woman in Me: ‘why did everyone treat me, even when I was a teenager, like I was dangerous?’. This reflection mirrors notions of ‘youth’, ‘beauty’, and ‘sexiness’ as a double-edged sword: empowerment is weaponised to produce insecurity, shame and control. Wannerberger deploys these attributes to question how a woman’s sense of worth is hence constructed through male desire.

As the loss of an intimate relationship with a partner manifests itself in the form of the empty city, the exhibition lingers on the emotional aftermath of desire, attachment and absence. The girls in the paintings never meet the viewer’s gaze. Instead, they contemplate, meditate, observe and feel. Like the Lisbon sisters in The Virgin Suicides, the girls evade direct access, refusing both the male gaze and narrative transparency. Their inner lives remain fundamentally unknowable, constructed from distance rather than encounter.

London anchors Wannerberger's scenes of love and heartbreak. Specifically depicted as architecturally and emotionally complex, with historical buildings existing alongside functional and modern contemporary structures. As meaningful moments become part of the past, sites like the Pontoon Dock Station or the Dutch Church in Moorgate become a faded memory. As the rupture unfolds, one becomes a spectator of their own life. Touching on the anticipation of a relationship ending, this feeling appears particularly poignant in Wannerberger’s drawings. Could we ever go back to the places that recalled a past love? Artworks such as What was left of you illustrate this sentiment: reflecting on this void, they represent the anticipation of knowing it might be the last time. One might recognise the brutalist bridges of Greenwich or the industrial sites of the Docklands. Their realistic representation is what makes them recognisable; yet it is their symbolic resonance as objects stripped of meaning that captures our intention. As two lovers once shared locations, inside jokes and tender moments, the past is erased to leave space for the future, the quiet reminiscence of past love becomes inseparable with the silence of the city.

Furthermore, Wannerberger’s girls are surrounded by objects that characterise their state of mind and accompany their search for meaning in the empty space. Collected as trophies on paper, for Wannerberger these architectural structures immortalise the places and experiences that cannot be separated from intimate memories. Drawn from the 1990s and the 2020s, they help construct a sense of narrative within the work. Star-shaped hair clips from the 1990s sit alongside iPhones; a Beauty and the Beast mirror is paired with a used red Durex condom; Ugg boots appear alongside a Mickey Mouse bandana. These juxtapositions subtly allude to the infantilisation of girls, who associate such objects with comfort and happiness. Forced to grow up too quickly, they retreat towards the imagined safety of childhood.

Scientifically known as Wollemia nobilis, the ‘dinosaur tree’ is a species alien to the United Kingdom. This makes it as intriguing as it is unique; its presence seems out of place within London’s modern and urban environment. By recreating and collecting experiences, places, and objects she can no longer access or relive, Wannerberger reclaims ownership of them. Immortalised through representation, the dinosaur tree symbolises the beginning and the end of love. Repeated throughout this body of work almost mechanically, the dinosaur tree foreshadows the slow burn that is the loss of identity from heartbreak, a mirror to the dismembered limbs of Wannerberger’s girls.

Download full press release here.